The Los Angeles Dodgers have plenty of Baseball Hall of Fame representation, but it’s worth examining these three stars’ cases further.

The Dodgers are one of baseball’s premier franchises for a reason, sporting a legacy of greatness that extends far beyond their time in Hollywood to the Brooklyn days.

That explains their heightened representation in baseball’s hallowed halls — 55 players, executives and managers who spent their time in Dodger blue have been enshrined in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Add in the team’s four honored broadcasters, and you’ve got what we like to call “domination” going on.

But is it possible that the franchise’s footprint at the Hall should actually be larger than it currently is? There are a few Dodgers legends who should probably have a plaque by now who are still languishing in history’s purgatory — or, at least, if they don’t merit induction, we should make the conversation louder.

These three Dodgers deserve to have their cases argued on a wider scale.

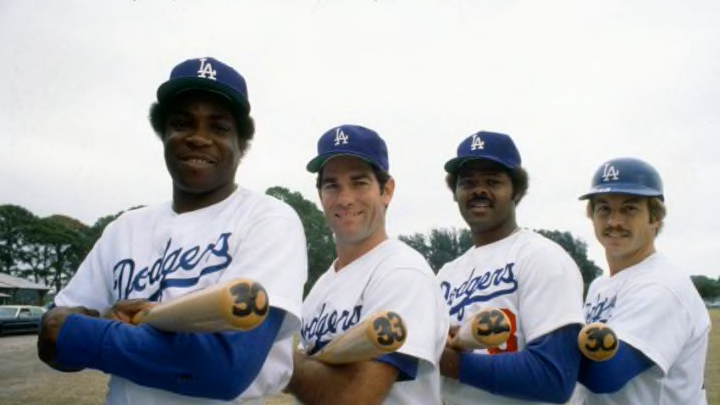

3. Steve Garvey

Dodgers icon Steve Garvey should’ve come closer to Hall of Fame induction.

Iconic Dodgers first baseman Steve Garvey would be a Hall of Famer if the statistical revolution hadn’t retrospectively devalued the way he played the game.

But how was he supposed to know every point of emphasis would change in the late ’90s?

Back in Garvey’s day as the face of the multi-time National League champion Dodgers, he wasn’t told that a walk was “just as good as a hit” — rather, he came up to the plate intending to smack singles and hit often and with power, which is exactly what he did.

A career .294 average offset by a meager .329 OBP would be unimpressive for a modern first baseman, but Garvey wasn’t planning to retire to glory based on the strength of his eye. The league MVP in 1974 (.312/21/111), that season kicked off an eight-year stretch of nothing but All-Star appearances, replete with three NL championships. At the time, you could make the argument that Garvey was the game’s biggest star on its largest stage.

He even rejuvenated himself with the Padres at age 35 in 1984, leading an entirely different team to the World Series with his veteran guile and still-potent bat.

If the Hall was truly a shrine for the famous, Garvey would’ve skated in on the first ballot. Unfortunately, his credentials somehow became less impressive over time, and he fell off the ballot in 2007 after 15 full years, peaking at 42.6% in his third year but never rallying with any sort of momentum, eventually petering out at 21.1%. Generally, someone who debuts at 41.6% these days sees a precipitous rise; not so, in this case.

We understand Garvey’s limitations and the reason for his exclusion, but the trajectory of his numbers is a bit baffling, especially for such a consistent on-field performer.

More Articles About Dodgers Hall of Fame: